Via Transportation (VIA): Road to Nowhere

Initial Disclosure: Funds managed by Bleecker Street are short Via Transportation (VIA). Please see the full disclosure at the end of this report.

Key Points:

We believe that VIA is a labor-intensive transit contractor masquerading as a software platform. We reviewed more than 100 contracts involving public sector-focused transit company Via Transportation (VIA). They show this ~$2.4 billion market cap recent IPO is more like a low-margin transportation services vendor than the high-margin, software-driven platform it claims to be.

We estimate that service hours, driver hours, and vehicle utilization drive the overwhelming majority of VIA revenues, not software licenses. VIA’s primary upsell avenue is for local governments to buy more vehicles and drivers, not more software.

VIA customers are focused on cost-cutting at VIA’s expense. Key VIA accounts like LA Metro have renegotiated pricing downward or outright removed VIA’s software in favor of competitors like Spare Labs.

VIA’s revenue base is precarious. The majority of VIA’s new deployments rely on temporary federal grants or COVID relief funding. When these subsidies expire, local governments frequently shrink or terminate their contracts. Per two former VIA employees, ~10-20% of churn came from grants expiring, and ~50-80% of pilot costs were subsidized by federal funding. Local budgets across the US face a fiscal cliff beginning in 2026 as Covid-era relief funds expire.

VIA routinely books large implementation fees and up to 18 months of software charges upfront, inflating ARR. One VIA cooperative purchasing agreement, for example, includes upfront software fees that comprise ~31% to ~153% of total first-year contract values.

VIA excludes core variable costs such as insurance expenses from cost of revenue and does not differentiate support costs from G&A. We believe VIA’s accounting treatment overstates gross margins and deviates from peers like Uber and Lyft’s reporting standards. The Company also presents dollar retention metrics using what we believe are non-standard, overly lenient definitions.

Taken for a Ride: The VIA Story

We believe VIA is trying to pass off a volatile transit services business as predictable and software-dominated. In reality, top customers like LA Metro are reassessing or downsizing their relationships with VIA, two transit agencies recently ripped out VIA software, and the public transportation sector is facing a fiscal cliff next year if COVID-era transit appropriations lapse.

We reviewed more than 400 RFP processes and over 100 of VIA’s signed local government contracts, including its largest accounts. Across these documents, we found overwhelming evidence that VIA is not a software-led business, a fact corroborated through interviews of former VIA employees, VIA’s competitors, and local government officials. Instead, VIA is a labor-intensive contractor dependent on federal subsidies, COVID relief funds, and elevated transit budgets from prior administrations. The contracts and board minutes we reviewed are available here.

The bulk of VIA revenues come from what we believe are commoditized services: driver hours, vehicle hours, and operational management. We estimate that ~72% of VIA’s revenue comes from services, with only ~28% from software. We believe VIA inflates upfront revenue, ARR, and gross margin by booking large upfront implementation fees and charging between ~31%-153% of first-year microtransit software revenues at contract inception.

In our view, the overwhelming majority of revenue expansion comes from customers adding more vehicles, longer service hours, or larger service zones, rather than software deployments, which makes meaningful gross margin expansion unlikely. Several transit agencies, including top VIA customer LA Metro, have already reduced contract size, renegotiated pricing, or removed VIA’s software layer and replaced it with offerings from competitors like Spare Labs.

VIA’s customer base appears to be stuck in a precarious financial situation that impairs revenue growth prospects. Various temporary federal grants, such as the Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Program (CMAQ) and the Carbon Reduction Program (CRP), fund the majority of new deployments, per former VIA employees and industry experts we spoke to. These grants create the appearance of high retention and predictability, but when they run out, agencies frequently shrink or terminate experimental transit programs. A pattern emerges across VIA’s portfolio: Palo Alto, Milwaukee, Ben Franklin Transit, Miami-Dade, and others have all reevaluated, reduced or exited their contracts as grant cycles end or budgets shift.

We believe VIA’s accounting presentation compounds these structural risks. VIA allocates key variable costs like insurance to G&A rather than cost of revenue. We believe this sleight of hand results in a margin profile that flatters the economics of VIA’s service-driven business. In our view, VIA also inflates gross and net dollar retention metrics by using overly lenient churn definitions that diverge from software norms.

Our findings suggest to us that VIA is a transportation contractor miscast as a SaaS-adjacent platform. We believe valuation should be in line with Lyft (LYFT), which trades at 2.2x 2027E gross profit. Should VIA trade at the same multiple, its shares are worth $11.80, 60% lower than their current price.

We Do not View VIA to Be a Software-Driven Company

VIA’s IPO narrative centers on the idea that it is a software platform transforming public mobility. Management highlights SaaS-like metrics, recurring revenue, and platform adoption as evidence of a technology company with long-term operating leverage. But a review of more than 100 local government contracts and RFPs tells an entirely different story: VIA is not a software-led company in any economically meaningful sense. It is a transit services contractor whose revenue is determined almost entirely by driver hours, vehicle hours, and operational labor, not by software licenses or platform usage.

VIA management advances the notion that software is VIA’s main draw, while services stoke the software adoption flywheel. In the Company’s Q3 earnings call, VIA reiterated this idea:

However, across VIA’s portfolio, we see that VIA gets paid primarily as a service provider, by vehicle and by hour, not for its software. Furthermore, as we lay out below, recent customer renegotiations show clients are content to ditch VIA’s software.

Various RFP microtransit proposals, including active agency bids, structure pricing primarily on the basis of driver hours, as the software agreement portions of such bids, which fluctuate based on fleet size, make up a miniscule portion of total contract values.

VIA’s software platform appears to us to be a distant second as far as driving revenue is concerned. In Arlington, Texas, one of VIA’s largest and longest-running accounts, the contract explicitly states that VIA is paid based on on-demand [driver] service hours. Annual costs are calculated by multiplying the city’s projected vehicle hours by VIA’s hourly rate. Software fees are immaterial at less than five percent of total contract value, and they do not scale with usage.

The same pattern appears in contracts across Los Angeles, Miami-Dade, Milwaukee, Met Council (Minneapolis), Ben Franklin Transit (Washington state), and dozens of smaller agencies. VIA’’s extensive RFP pricing sheet lists every bid category in terms of per-driver-hour charges for different vehicle types, with software fees tied only to fleet sizes.

Even VIA’s largest and most visible contract, LA Metro, reveals the hollowness of the software-driven narrative. As LA’s Metro Micro program matured post-VIA pilot, the agency pushed out VIA’s software, replacing it with software from competitor Spare Labs. LA retained VIA for the lower-margin operations contract, but only after renegotiating VIA’s prices down. We lay out the sequence of events below in Case Study 1.

Minneapolis’s Met Council reached the same conclusion, eliminating VIA’s transit software layer in 2024 and awarding the software contract to Spare Labs. We detail the course of events in the Appendix, in Case Study 2.

We believe these examples demonstrate that VIA’s software does not have meaningful defensibility in TaaS. Customers treat VIA like any other outsourced transit contractor. When performance falters or costs rise, clients simply rebid the contract and are increasingly awarding the software portion to competitors. This behavior is fundamentally incompatible with SaaS economics, which depend on sticky, expanding relationships. Even VIA’s internal dynamics reflect a services business rather than a technology platform.

In interviews, former VIA executives described VIA’s Remix planning tool as an offering that the Company used primarily to help win service bids, not as a scalable standalone software offering. They explained that Remix “is typically not sold as a TaaS plus SaaS contract” and employees instead view Remix as a one-time cost related to bid preparation, rather than a recurring or usage-based software relationship. Sometimes, VIA gives Remix software away to customers for free, as in the Cal-ITP program.

The evidence becomes even clearer when examining how “upsells” occur. Management repeatedly presents upsell motions as proof of growing software penetration, but contract documents show that expansions come from more drivers, more vehicles, longer service hours, and broader geographic coverage. For example, in Mobile, Alabama, VIA has touted 17x revenue growth. The city’s documents, excerpted in the Appendix, attribute these increases primarily to VIA acting as the outsourced transit management provider and operator across expanded service zones and increased vehicle hours. The city appears to be in essence paying VIA to operate more vehicles for longer with a fee schedule oriented around services.

Finally, agreements that VIA points to as “recurring platform revenue” are often not software commitments at all: they are minimum service-hour guarantees embedded in grant-funded transit budgets. Several customers are obligated to pay VIA tens of thousands of annual billable vehicle hours regardless of actual ridership. These guarantees appear to inflate VIA’s perceived revenue durability and mimic SaaS retention metrics, but the underlying driver is not technology adoption: It is preallocated federal grant funding, which agencies often lose after three to five years.

We believe VIA monetizes drivers, vehicles, and operational logistics, not a software platform. Its contracts look very little like SaaS agreements to us. Instead, they appear exactly like traditional transit sourcing agreements, down to the not-to-exceed budgets, insurance obligations, and service-hour billing structures. Whenever cities reconsider their programs, they treat VIA accordingly: they scale service hours up or down, swap out the software, or rebid the entire contract.

VIA Frontloads Software and Implementation Fees, Which We Believe Flatter Year 1 Revenues and ARR

Via states the substantial majority of its revenue comes from recurring and volume-based subscription fees. However, we found these subscription fees are rebranded service revenues. At the same time, a material portion of revenue comes from one-off implementation and software setup expenses, which appears to flatter revenues, margins, and ARR. Here is VIA’s description of its revenues:

VIA’s Springfield, Ohio launch suggests to us that what the Company calls subscription revenue is actually thinly veiled service pay. We observe within VIA’s agreement below that its service revenues, while called “Monthly Subscription Fees”, are not the product of software or technology usage. Rather, they are a function of active driver hours for transportation services. This is, in our view, equivalent to calling the bill received from one’s lawyer or electrician a subscription fee: even if recurring, it is the result of payment for services and labor. Implementation fees also amount to 10% of Year 1 service revenues:

In the same contract, VIA breaks out the cost of true software fees, and they are a fraction of total contracted costs, as seen in the table below. VIA’s implementation fees for software are a significant portion of yearly software totals, with ~34% of the cost of software revenue Year 1 charged upfront in this example:

This dynamic of large up-front implementation fees and revenue being driven by variable driver hours vs. miniscule software fees is consistent across contracts we reviewed. It is also visible in VIA’s own public pricing catalog (PDF p. 72) that underlies the OMNIA Co-Operative agreement.

Driver hours are the largest contributor to VIA revenue and will always be the primary factor determining growth or contraction in VIA deployments, as per our sensitivity table below based on the OMNIA agreement. We estimate that TaaS revenue is the overwhelming revenue contributor for turnkey contracts at small, medium, and larger fleet sizes, constituting 96-98% of total revenue:

VIA also appears to extract a significant run-rate revenue and margin boost from upfront software charges. Based on the OMNIA catalog list prices, we estimate a large portion of software revenues is pulled forward for new customer starts, with VIA charging a ~$28.3K installation fee for fleets of up to 20 vehicles and a ~$38.6K install fee for larger fleets. These fees result in upfront charges of 31-153% of annual fees, depending on fleet size:

This dynamic is even stronger for paratransit services, with a $38.6K installation fee for fleets up to 20 vehicles and a $48.9K installation fee for larger fleets. These higher fees result in upfront charges comprising 50-240% of annual software fees, depending on fleet size:

We think VIA’s upfront fees exaggerate its early project revenues and ARR while also inflating margins. However, in our view, VIA has more margin distortion tricks up its sleeve.

We Believe VIA’s Accounting Treatment is Materially Misleading

We think VIA inflates gross margins by misclassifying core operating costs. While the Company emphasizes eventual “platform margins” approaching those of SaaS companies, public contract requirements reveal a cost structure that appears to us far closer to a traditional transit operator’s. Unlike peers Uber and Lyft, VIA records some of these costs inside G&A, which we think aids the illusion of a high-margin software business in the making.

Numerous contracts we reviewed require VIA to carry commercial fleet insurance; auto liability insurance for all contracted vehicles; workers’ compensation insurance; and, in many cases, to staff dispatch personnel and ensure vehicle maintenance and inspection as required by Federal Transit Administration (FTA) regulations. For example, insurance requirements in VIA’s contracts often require $1-5 million per-occurrence for vehicle and liability coverage, with commercial fleet insurance required for all VIA-operated vehicles.

VIA classifies such expenses as G&A, whereas Uber and Lyft classify insurance, driver incident costs, safety programs, and associated support expenses as cost of revenue:

We estimate that the inclusion of insurance costs, while not as burdensome as the insurance for ride-sharing platforms, reduces VIA’s gross margins by 3-4%.

Furthermore, VIA’s contracts often require it to staff local customer support centers and live call centers. While both Uber and Lyft break out end-user operations and support costs as separate line items in their reported operating expenses, VIA places these costs into an undifferentiated G&A line item. We believe this treatment streamlines VIA’s expenses to appear SaaS-like, despite the domination of the services business.

We estimate that adjusting VIA’s cost of revenue to include insurance expenses reduces our estimated services gross margin to ~26%, while breaking out support staff from corporate overhead brings contribution margins to an estimated ~22%:

We estimate that ~72% of VIA revenue is services, while only 28% is software:

We believe that stripping away VIA’s gross margin inflation reveals a service-dominated business with margins that are structurally lower than reported. Likewise, we think VIA overstates its ability to retain customers and their revenue.

VIA Retention Metrics Appear to be Exaggerated

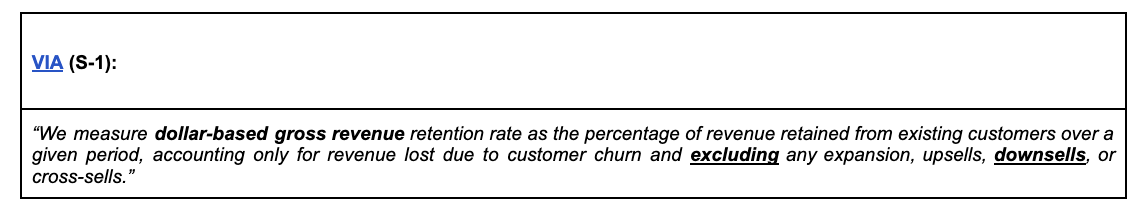

We view VIA’s dollar retention definitions as abnormally lenient for a software business, even one with a strong services component. VIA’s Gross Revenue Retention (GRR) metric, which it reports as greater than 95%, is not burdened by customer contraction, or “downsell”:

Such a definition is unusual compared to most standard definitions for investors across both seat- and usage-based recurring revenue models, which often include both contraction and churn in their GRR metric to establish conservative, transparent views on customer spend:

By excluding downsell in its GRR calculation, VIA’s methodology does not capture the volatility of transit agency budgets, which have frequent contractions in spend. Nor does VIA’s GRR capture the shifting scale of transit programs, as highlighted in our case studies of Milwaukee and Ben Franklin Transit in the Appendix. Both agencies are undergoing reductions in VIA service usage but have not completely churned off.

We also see issues with VIA’s Net Revenue Retention (NRR) metric, which it stated exceeded 120%. In computing a yearly NRR cohort, VIA requires customers in the cohort to have had revenue in each of the four quarters of the prior year:

In our view, this definition reduces cohort inclusion to those customers that are already maturing while diminishing the impact of those customers that completely churned off intrayear, as they are not present to recognize revenue in each of the four quarters of the prior calendar year. Such a definition contrasts with a more standard trailing twelve-month NRR calculation.

Taking an illustrative example of a cohort population, in Year 0, we begin with three customers growing throughout the year:

Then, we use the examples below to contrast what we believe is an accurate interpretation of VIA’s NRR definition versus a more standard NRR definition. In the next year, Year 1, Customer A churns off the platform in Q4. Overall, the two NRR computations are very similar. There are no deviations between quarterly calculations, as Customer A was present in the prior 4 quarters to recognize revenue. The minor variance in annual NRR figures is due to VIA averaging quarterly periods, which smooths variance and produces a slightly higher number, compared to Standardized NRR taking the simple quotient of totals between Year 1 and Year 0:

In Year 2, however, VIA excludes Customer A from the VIA NRR cohort because of its Q4 churn event. As a result, VIA counts only Customers B and C in its quarterly calculations, while Standardized NRR includes Customer A for Q1-Q3. These differences yield significant variance between methodologies, with VIA’s definition yielding a healthy 116% NRR while Standardized NRR is only 85%:

Accordingly, we believe VIA’s NRR gives a significant boost to retention figures by undercounting customers that have churned late in the year or soon after a program start when compared to a standard NRR definition.

We believe both of VIA’s retention metrics are mathematically easier to achieve and aid in the illusion of software-like retention metrics, particularly in a sector whose customers are often impacted by budget reductions and frequently churn from pilot programs.

Customer Defections and Downsizings: Death by a Thousand Cuts

VIA’s customer losses rarely present as clean, headline churn. Instead, erosion occurs through a steady pattern of contract downsizings, rebids, software unbundling, and non-renewal of grand funded pilots. This behavior is fundamentally inconsistent with a SaaS-like business model built on sticky software adoption and strong net dollar retention. It is, however, entirely consistent with a discretionary, labor-priced transit services vendor operating under tightening local budgets.

Dozens of transit agencies whose documents we reviewed treated VIA not as a mission-critical platform, but as a vendor whose scope routinely gets resized or reconfigured as costs rise, grants expire, or procurement priorities shift. In many cases, agencies preserved some portion of service while removing VIA’s software layer or reducing vehicle hours, outcomes that do not suggest to us that VIA has the resilience of a true software platform. Some agencies are considering ditching VIA altogether, which is unsurprising given the failure rate of microtransit programs is 25% in the first two years and 40% within three years.

Based on our review of active RFPs and city board minutes, there is a growing trend of decoupling software from operations occurring in large agencies to avoid the pitfalls of vendor lock-in create more competitive processes, as industry participants noted:

“In the turnkey environment, agencies are now looking at it and saying, ‘Let’s decouple those and let’s contract for the software separately to the supply side.’ We’re seeing a lot of that come up now… OmniTrans in San Bernardino is doing it as well, and Corpus Christi broke it apart, too: conversations are happening where cities and agencies are realizing it’s not a good idea for your software vendor to own your supply – having the wolf watch the hen house.”

RideCo Principal

“The transit authority or city doesn’t trust companies like VIA to run both the operations and control the optimization engine. VIA have their own commercial biases, they’re incentivized to expand the fleet, do more trips and expand the service - and that isn’t always aligned with the customers goals essentially. Miami-Dade released an RFP earlier this year that was turnkey but they actually cancelled the RFP and went back and revised it to be software only, so they’ll be decoupling it from the operations. Hillsborough was another one.”

Spare Labs VP

LA Metro is the top VIA customer with a total contract size of ~$135 million including extensions, and it recently exhibited the kind of hesitation over vendor control and frustration over pricing that illustrates to us how little control VIA has over its own destiny.

Case Study 1: Los Angeles Forced VIA to Slash Prices, Split Software from Services, and Contracted it Away

VIA’s top customer by total contract value, Los Angeles’s Metro Micro, decided to renegotiate VIA’s contract and then divide it up before giving the software portion to a competitor, leaving VIA with only an even lower-margin services contract than it had before.

The Metro Micro-VIA relationship started off with a pilot before moving to turnkey services and expanding to a larger coverage area, requiring more hourly drivers. However, in 2023, the cost per trip became too high for the city at $42/ride, so Los Angeles asked contractors to lower pricing to keep the program. VIA, through its subsidiary Nomad Transit, slashed its price by ~15% across the North and South LA regions, resulting in a reduced cost of ~$24 per hour across the North and South service regions:

Metro Micro granted VIA the diminished three-year services contract worth ~$66 million in November 2024, with an additional three-year option for the city to extend service for ~$69 million:

Simultaneously, however, Metro Micro began exploring splitting services and software to lower costs further.

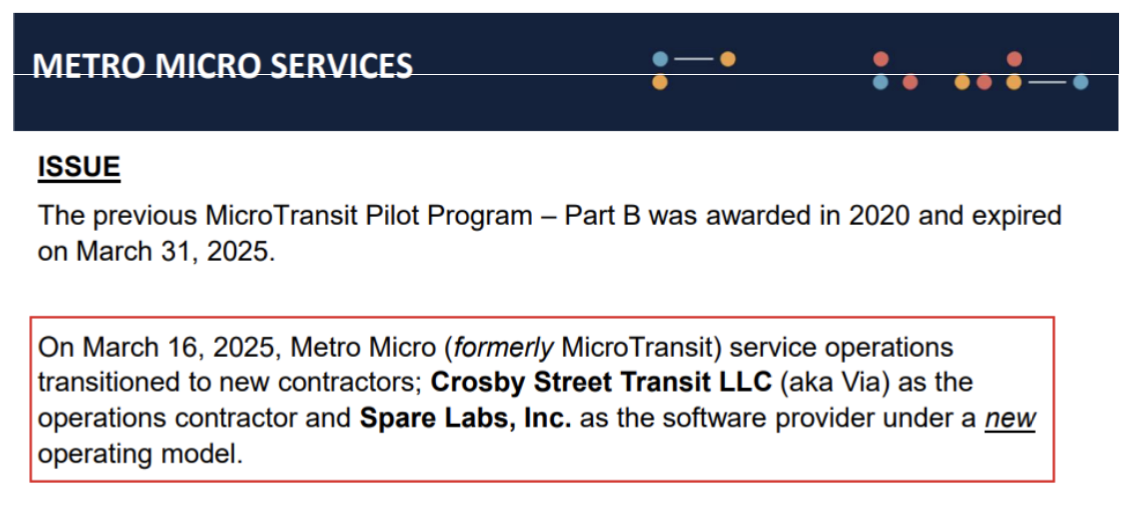

In July 2025, Metro Micro formally announced it had split the contract. VIA was to perform service and operations work, while competitor Spare Labs won the contract to provide the software:

Metro Micro touted this development in which VIA had lost platform control as a “new operating model”:

In the Appendix at the end of the report, we include further case studies of VIA customer issues we believe are illustrative of VIA’s margin, retention, and unbundling pressures. These include top customer Arlington; recent adopter Minneapolis; skeptical pilot participant Palo Alto, and six other VIA clients who are reassessing or cutting VIA.

We Believe Temporary COVID Funds Fueled VIA’s Growth and Are Now Depleted

The favorable budgetary conditions that enabled VIA’s rise appear to be in danger of reversing. The FTA and Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) have historically subsidized public transit agencies heavily. The most recent funding program authorized from 2022-2026 as part of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) is set to expire in September 2026.

The IIJA provided a ~67% increase in annual funding for public transportation to ~$21 billion as compared to the prior FAST Act while increasing the FTA and FHWA’s transit-focused CMAQ program. The IIJA also grew FTA formula funding by ~$8 billion+ per year for existing programs such as 5307 Grants and 5311 Grants in addition to allocating billions for various new federal programs and grants.

In addition, in response to COVID-related drops in ridership, the Biden administration allocated an extra ~$69.5 billion of emergency COVID-19 funding to support transportation budgets:

This funding wave created the ideal environment for alternative transportation startups such as VIA to flourish, resulting in an acceleration of launches for grant-funded microtransit pilot programs by local governments and municipalities. See, for example, how an FTA grant contributed 40% of LA Metro’s pilot budget:

Based on our review of RFPs, contracts, and city board minutes, the vast majority of new VIA launches and existing pilot agreements are heavily subsidized by federal climate-related programs and capped usage grants, such as CMAQ and CRP, that allow subsidized federal funding support for transportation projects for up to 3-4 years via a ~50-80% federal match.

However as the IIJA and COVID relief funds spawned numerous transportation programs, public transit ridership returned at a glacial pace, resulting in transit agencies leaning heavily on federal funds for operating budget shortfalls, per the 2025 American Public Transportation Association (APTA) Fact Book:

National ridership still remains at ~84% of pre-COVID levels as of November 2025:

The combination of the financing glut and anemic ridership recovery has led to the depletion of COVID funds. Agencies across the nation are beginning to announce service cuts for routes, layoffs, and fare hikes due to reduced operating budgets heading into 2026. Numerous agencies have even had to use re-allocated state funds to help bridge the funding gap until IIJA funds might get reauthorized after their Q3'26 expiry.

In revising its outlooks on two transit agencies to negative in its October 2025 U.S. Transit Update, S&P Global noted uncertainties surrounding the industry’s fiscal cliff and ridership:

“We believe full recovery to pre-pandemic ridership is unlikely for many years, if at all… Based on our most recent activity estimates, we expect the recovery in public transit will lag that in all other transportation modes, with ridership reaching only about 90% of pre-pandemic levels by 2027… We're examining instances where states and local governments have stepped in to provide increased or new financial support for transit operators facing operating funding gaps, as well as other instances where transit operators are facing political pressure on financial support. Our evaluation of ratings and outlooks will consider these pressures, either credit positive or negative, and crucially, whether the funding is a one-time measure or represents a recurring source of support capable of bridging long-term funding gaps.”

The potential of a timely and large-scale capital injection through an IIJA replacement seems unlikely, as even transportation advocacy group T4A recognizes that prior reauthorizations have required numerous short-term extensions, which limit the ability to fund new projects.

As industry insiders and former VIA employees informed us, the free money train has gone off the rails:

“In the last administration, there was just a lot of money up for grabs for testing these pilots and getting free money. It’s something these agencies can’t refuse so they get these grants - now I have no idea.”

Former VIA Operations Executive

“Some of the federal grant funding VIA used has expired, some of the grant funding sources have gone in waves and the prior administration was much more interested in it than the current administration.”

Former VIA Strategy & Operations

From our research and former VIA employees, it seems the go-to-market strategy for VIA after a pilot launch and grant funding expires is to convert cities to 5307 or 5311 funding, which are formulaic and a fixed pot of funding of existing transportation budgets based on population size and pre-allocated state funding.

If the effort to secure more long-term federal funding fails, the programs in question are structurally at risk. Per former VIA employees, losing grant funding is a key driver of churn when ROI is not proven.

“10-20% of pilots churned because the grants ran out. There is a fair bit of turnover, microtransit is not a core service that any county or public transit agency is providing - so they’re more likely to cut microtransit than other services.”

Former VIA Strategy & Operations

A key mechanism for funding projects like microtransit pilots via IIJA grants, Highway Trust Fund (HTF) accounts, has recently come under scrutiny from the Trump administration. In November, the Department of Transportation (DOT) proposed to eliminate HTF accounts and prevent states from flexing highway funds for transit projects, which would halt use of this grant funding for non-highway use cases.

With excess funding sunsetting, a less supportive federal backdrop, and fiscal deficits increasingly common, many local governments are entering the budget justification phases of programs launched in prior years. Industry experts view microtransit as on the chopping block.

“The current FTA and DOT is not super friendly to public transit and losing the ability to flex highway spending is a concern… The fiscal cliff is a danger, there are headlines of services ending and like I said before, it’s a non-essential that can be cut. I think there will be more examples going forward of specific agencies cutting microtransit.”

Former VIA Strategy & Operations

“I’m not confident microtransit is a growing market right now because of all the funding drying up. The fiscal cliff everyone is talking about is referring to the grants and subsidies that VIA and others received a lot of.”

Spare Labs VP

“This funding issue is the biggest risk. If cities or governments have to tighten their belts and less money goes down - microtransit is a nice service, but they’re not continue to fund it if they have to cut something - we’ve already seen it… that’s why you see so many pilots start up and go away. CMAQ or CMO you can only use for 3-4 years and that’s competitive funding.”

RideCo Principal

We believe transit agencies and local governments across the board are less willing to spend on experimental or supplemental programs such as microtransit in the face of fiscal uncertainty at both the state and federal levels. As COVID-era funding and grants wind down or get fully allocated, we expect new launches to decelerate in 2026, while programs in the 2021-2022 cohorts will be reexamined closely for cost effectiveness next year upon contract maturity, as we discuss in the cases we present above and in the Appendix.

Valuation and Downside

Public market investors appear to value VIA as a software platform with recurring revenue, operating leverage, and long-term margin expansion potential. That framing underpins VIA’s current valuation and place VIA alongside software-enabled mobility and SaaS-adjacent peers rather than as a traditional transit operator.

As we have shown, the underlying economics described do not support this classification. Across the public agreements we reviewed, VIA’s revenue is primarily driven by labor hours, vehicle hours, and operational scope, with software fees typically de minimis, front-loaded, or not scalable. Expansion occurs when service volumes increase, not when software penetration deepens. Gross margins are constrained by labor, insurance, and operational requirements that do not diminish with scale the way software costs do. These characteristics align it more closely with outsourced transit services than with software platforms.

Despite this, VIA continues to trade at valuation levels that imply durable software economics. The market appears to be capitalizing VIA’s revenue stream as if it were sticky, recurring, and scalable. That assumption is difficult to reconcile with a business model where revenue durability depends on discretionary local budgets, temporary grant funding, and renegotiable service-hour commitments.

Traditional transportation and transit operators, whether private contractors or publicly traded mobility services firms, are valued at substantially lower multiples due to their labor intensity, limited operating leverage, and exposure to budget cycles. These businesses generate cash flow through execution and utilization, not through compounding software adoption. VIA’s contracts, customer behavior, and cost structure place it firmly in this category.

Moreover, a meaningful portion of VIA’s recent growth has been supported by temporary federal grants and Covid-era relief funding;. As these programs sunset and agencies reassess discretionary services, revenue growth and retention face incremental pressure. Valuations predicated on steady, software-like expansion do not adequately account for this cyclicality and funding risk.

In our view, VIA’s current valuation reflects a narrative premium rather than economic reality. We believe that investors should focus on contract structure, margin sustainability, and funding durability, we believe the market will be forced to re-rate the stock towards levels more consistent with labor-intensive transit services rather than software platforms.

We believe ridesharing platform LYFT is a good valuation benchmark for VIA. LYFT trades at 2.2x consensus gross profit for 2027. Should VIA trade at the same multiple of consensus gross profit, its shares are worth $11.80, which constitutes 60% downside. As we discussed above, we think VIA’s revenue stability and quality issues imperil both revenue growth and profitability prospects, presenting additional risks to that price target.

Conclusion

Via Transportation markets itself to public investors as a software platform with recurring revenue, operating leverage, and SaaS-like economics. A review of the Company’s own contracts, procurement documents, and customer behavior tells a very different story.

Across more than 100 agreements we reviewed, customers compensate VIA primarily for labor-intensive transportation services -- driver hours, vehicle hours, and operational scope -- not for software usage. Software fees, relative to service fees, are small, fixed to fleet sizes, and charged upfront at contract inception. The majority of revenue expansion occurs when cities extend driver hours or widen service zones, not when they deploy additional software features. This is the economic profile of a transit contractor, not a software platform.

Customer actions reinforce this conclusion. Several of VIA’s largest and most sophisticated public-sector clients have downsized contracts, renegotiated pricing, or separated software from operations entirely, awarding the software layer to third-party vendors while retaining VIA as a lower-margin services provider, if at all. These outcomes are inconsistent with durable, software-driven platform adoption and instead reflect discretionary sourcing decisions typically taken for outsourced transit services.

VIA’s reported financial presentation further obscures this reality. The Company’s margin and retention metrics that resemble those of software companies but are driven by service volume, minimum-hour guarantees, and grant-funded budgets. When adjusted for the underlying economics of the contracts, VIA’s business exhibits limited operating leverage and structurally constrained margins.

Finally, the durability of VIA’s revenue base appears increasingly fragile. Federal grants and COVID-era relief funding have supported a substantial portion of recent growth. As these programs sunset and local budgets tighten, transit agencies are reassessing pilot programs, cutting discretionary services, and rebidding contracts with a sharper focus on cost. In that environment, labor-priced and grant-dependent services face materially higher churn risk than true software subscriptions do.

We believe VIA’s valuation rests on a narrative that is not supported by its contracts, customer behavior, or unit economics. Rather than a scalable software platform, VIA appears to be a capital- and labor-intensive transit services provider operating in a budget-constrained, subsidy-dependent market. As the gap between narrative and reality closes, we believe investors will be forced to re-rate the business accordingly.

Appendix: Further Customer Case Studies Show VIA Losing Share, Being Reassessed, or Reliant on Services to Expand

Below, we include 8 additional case studies showing VIA’s precarious position with existing customers. These cases show how VIA can be replaced, downsized, or potentially removed entirely. They underscore what we believe to be VIA’s role as a commodified, service-driven provider whose customer base is funding-constrained.

Case Study 2: Minneapolis Metropolitan Council Drops VIA as Software Provider

In September 2022, VIA launched in Minneapolis as the software provider for the Metro Transit micro service:

However, in October 2024, after conducting an RFP process, Minneapolis replaced VIA with Spare Labs:

Industry experts informed us this was due to Met Council’s lack of confidence in VIA’s software capabilities:

“In the software-only side for VIA, last year Metropolitan Council churned off VIA due to their multimodal capabilities, their customer support, and self-serve capabilities of the software - in addition to Met Council’s vision for combining the software solutions for both microtransit and paratransit, and they weren’t confident in VIA’s abilities to do paratransit so that was a big loss for VIA as Minneapolis is a top 3 or 4 transit agency in the country.”

Spare Labs VP

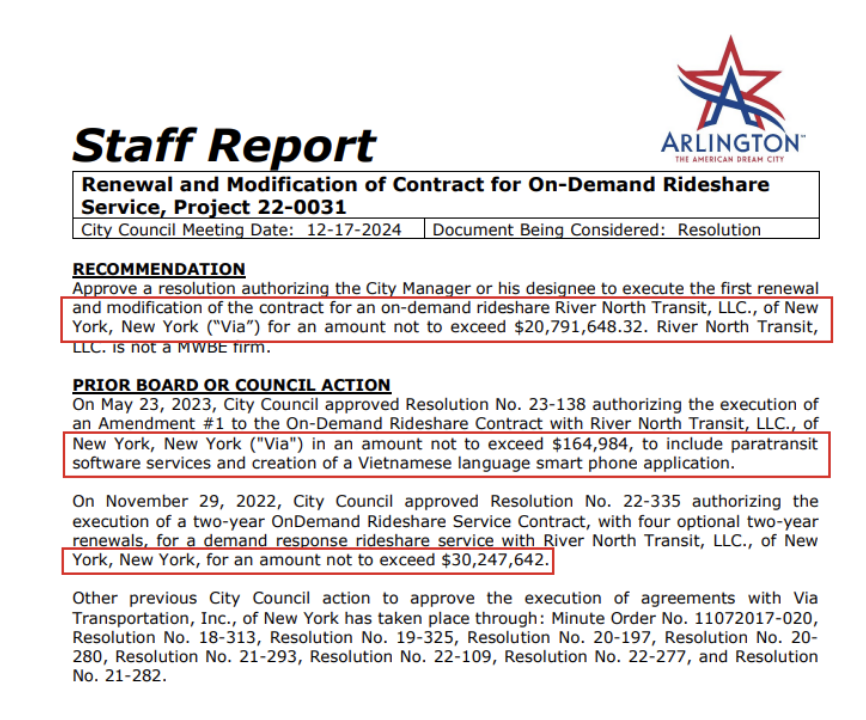

Case Study 3: Arlington, Texas Pares VIA Back

Arlington, Texas has been a VIA customer since 2017. In December 2024, Arlington slashed its $30.2 million ceiling contract by 31%, to $20.8 million:

The vast majority of Arlington’s contract is transport-as-a-service, as can be seen from the “Micro TaaS” line item below, which is 96% of revenues in 2026:

Arlington computes its cost breakdown per on-demand service hour, which the City defines to be “an hour that one driver is providing service to this Contract”. Such terminology cements the service-driven nature of the agreement:

Case Study 4: Palo Alto Reluctant to Extend Pilot Program

As reported in local news, Palo Alto launched its VIA-operated pilot in 2023 funded by Santa Clara VTA grants. As those funds sunset in 2025, the local government has discussed winding down the program and debated its viability without grant funding.

Case Study 5: Milwaukee County Transit - Reduction in Usage

The Milwaukee County Transit System (MCTS) launched a same-day paratransit pilot program with VIA in 2024 funded using a contingency budget:

By June 2025, per county board minutes the program saw higher than expected cost per trip as demand increased, with the board recommending its exclusion from their 2026 budget without additional funding sources or budget allocation:

In November 2025, the city projected further transit budget deficits for 2026 and included the paratransit operations in its cost cuts, with a limited version of the pilot program going forward:

When asked about the outlook for funding transit services, a county official shared that VIA’s position is challenged:

“Like everything in the transportation and transit industry, costs are increasing 10% to 20% from 2024. You look three years out, we could be looking at a 30% increase.. That’s exactly why I said what I said about the financial constraints. Companies like Via have to understand that. They need to offer something else to the public entity to continue with their services… I would say even a 15% to 20% increase [in three years] would be pretty untenable.”

Milwaukee County Transit Official

Case Study 6: Baldwin County Replaces VIA Software with Spare Labs

Baldwin County deployed VIA’s microtransit software to power its BRATS On-Demand microtransit service in 2020.

However, the region ran an RFP process in late 2024 and selected Spare Labs as the software layer for its microtransit service.

Ultimately, Baldwin County decided to terminate their VIA contract in Q2’25, with services ending in Q3’25.

Case Study 7: Ben Franklin Transit Reducing Microtransit Budget; VIA Lost Paratransit Software Bidding

Ben Franklin Transit (BFT) in Washington State uses on-demand and microtransit operations services from VIA. In November 2024, the agency renewed its contract using the 791 Cooperative Agreement, noting that vehicle hour reductions may be necessary for the service in the future based on budget constraints, grant revenues, and redundancies between the bus system and VIA’s service area:

In its November 2025 board meeting, BFT discussed re-assessing its agreement with VIA to improve efficiency and reduce redundancies between the program and bus system:

As per its 2025 Transit Development Plan, BFT wants to ensure buses remain the primary transportation method:

In the same November 2025 meeting, BFT ran an RFP for paratransit software and awarded the contract to RideCo despite VIA’s significantly lower cost, noting that VIA lacked the functionality to support paratransit operations:

Case Study 8: Hillsborough County, Florida Drops VIA From Paratransit Contract

VIA’s paratransit difficulties also surfaced in an RFP process with Hillsborough County in which Hillsborough terminated a previously awarded paratransit software contract with VIA due to “inability to meet required functionality”, awarding it instead to competitor Ecolane:

Case Study 9: VIA Loses Hampton Roads, Virginia Paratransit Operations

VIA also had to cede running paratransit operations for Hampton Roads Transit, as reported by local news. An industry expert confirmed this loss for VIA, adding that it put VIA’s associated software contract at risk:

“In Hampton Roads, VIA was running their paratransit services as a turnkey operation and it did not go very well and they were able to bring on a third party, Easton Coaches, to run operations for them and they were able to stay on as a software solution and it’s likely that contract is at risk over the next 18 months. That story is definitely still hurting them across the industry.”

Spare Labs VP

Via’s April 2024 agenda packet confirmed the transition to another operator and customer grievances:

Case Study 10: Mobile, Alabama - Upsell is driven by Transit Services, not Software Platform

In its inaugural earnings call, VIA highlighted Mobile, Alabama as an upsell case study and a customer for additional solutions including planning and scheduling, noting revenue increased 17x as a result:

However, per Mobile’s September 2025 Agenda Packet, the revenue expansion was driven by Mobile’s outsourcing of transit management to VIA, including costs associated with labor, staffing, maintenance, insurance, and services:

The fee schedule focused on transportation operations:

Furthermore, approximately ~33% of the total contract value is contingent on annual Federal Transit Awards awards being appropriated by the city:

Terms of Use

Use of reports prepared by Bleecker Street Research LLC (“BSR”) and this website is subject to and governed by the below Terms of Use (the “Terms”). The Terms govern all reports published by BSR (each a “BSR Report”) and supersede any prior Terms of Use governing the access and use of this website and BSR Reports, which you may download from this website. By downloading, accessing, or viewing any materials on this website, you hereby agree to the following Terms.

Bleecker Street and Its Related Parties

BSR is under common control and affiliated with Bleecker Street Capital LLC (“BSC”), Bleecker Street Capital Management LLC (“BSCM”), and affiliated funds, including but not limited to Bleecker Street Minerva LP (“Minerva”) and Bleecker Street Partners LP (“BSP”) (collectively, BSC, BSCM, and affiliated funds, including Minerva and BSP, are referred to herein as “BSC”). BSR is an online research publication that produces due diligence-based reports on publicly traded securities, and BSC and BSCM are investment advisers registered with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. The reports on this website are the property of BSR. BSR and BSC, collectively with their respective affiliates and related parties, including, but not limited to any principals, officers, directors, employees, members, clients, investors, consultants and agents, are referred herein to as “Bleecker Street”, “us”, or “we”.

BSR is a for-profit journalistic organization that researches and provides opinion journalism about issues of concern to the general public, including about the securities of public issuers. BSR finances its journalism through a non-traditional revenue model where it earns revenue from positions that BSC takes in the securities of issuers on which BSR reports. This business model requires Bleecker Street to take material financial risk, which our partners have exposure to. To manage risk, we must close open positions as we deem prudent. We do not provide “price targets” for securities, although we may express our subjective opinion of the value of a security, which differs from a price target in that we neither know nor claim to know how the market might value such security. We therefore typically do not hold, and provide no assurance that we will hold, a position in a reported-on security until it reaches a price target, nor do we necessarily hold, or provide any assurance that we will hold, positions in securities until such securities reach the price that reflects our opinion of value. Many factors enter into investment decisions aside from opinions of the value of the security, including without limitation, borrow cost, “short squeeze” potential, risk sizing relative to capital and volatility, reduced information asymmetry, the opportunity cost of capital, client expectations, the ability to hedge market risk, our perception of the efficacy of market regulators and gatekeepers, our perception of the resource imbalance between us and any Covered Issuer (defined below), and our subjective perceptions. Therefore, you should assume that upon publication of a report, we will, or have begun to, close a substantial portion – possibly the entirety – of our positions in the Covered Issuer’s securities.

Reports Are Solely Attributable to BSR

The BSR Reports on this website are opinion journalism. On this website and through the BSR Reports, BSR is providing its journalistic opinions about issues of concern to the general public. You understand and agree that the opinions, information, and reports set forth on this website are attributable only to BSR, which bears sole responsibility for the information on this website and content of the BSR Reports; provided, however, that persons affiliated with Bleecker Street have provided BSR with publicly available information that BSR has included in the BSR Reports and on this website, following BSR’s independent due diligence.

Website and Report Use Is at Your Own Risk

Any and all use of BSR’s research and BSR Reports is entirely at your own risk. Neither BSR nor BSC is liable for any losses or damages you may incur as a result of your use of this website, including but not limited to any direct or indirect trading losses you may incur as a result of any information on this website, any BSR research, or any BSR Report. You agree to do your own research and due diligence with respect to any information on this website, and to consult your own financial, legal, and tax advisors before making any investment decision with respect to transacting in any securities of an issuer discussed on this website (a “Covered Issuer”).

BSC’s Trading Practices and Positioning with Respect to Covered Issuers

As of the time and date of each report, BSC (defined below) is short the securities of, or derivatives linked to, the securities of the Covered Issuer, unless otherwise stated in the report. BSC therefore will realize significant gains in the event that the prices of a Covered Issuer’s securities decline. Upon the publication of each report, we may cover, and typically will cover, a substantial majority of our short positions. BSC’s covering its short positions upon the publication of a report is not a reflection of a lack of conviction in any opinions or the facts presented on this website or in any BSR Report. Rather, the act of covering BSC’s short positions upon the publication of a BSR Report is intended solely to manage risk in a prudent manner, consistent with the obligations of a fiduciary of our investors’ money. BSC are likely to continue transacting in the securities of Covered Issuer for an indefinite period after a report on a Covered Issuer, and we may be net short, net long or neutral positions in the Covered Issuer’s securities after the initial publication of a report, regardless of our initial position and views herein.

Notice to UK Residents

If you are in the United Kingdom, you confirm that you are accessing research and materials as or on behalf of: (a) an investment professional falling within Article 19 of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Financial Promotion) Order 2005 (the “FPO”); or (b) high net worth entity falling within Article 49 of the FPO (each a “Permitted Recipient”). In relation to the United Kingdom, the research and materials on this website are being issued only to, and are directed only at, persons who are Permitted Recipients and, without prejudice to any other restrictions or warnings set out in these Terms of Use, persons who are not Permitted Recipients must not act or rely on the information contained in any of the research or materials on this website.

No Recommendation or Solicitation; No Warranties

All information and opinions on this website and in BSR Reports are for informational purposes only. You understand and agree that no information on this website or in any BSR Report is investment advice or a recommendation or solicitation to buy securities. In any given BSR Report, BSR is solely articulating its reasons at the time of publication for the positions it may have in the securities of a Covered Issuer. To the best of BSR’s ability and belief, all information contained herein is accurate and reliable, and has been obtained from public sources we believe to be accurate and reliable, and who are not insiders or connected persons of the securities of a Covered Issuer or who may otherwise owe any fiduciary duty or duty of confidentiality to the Covered Issuer. However, such information is presented “as is,” without warranty of any kind, whether express or implied. BSR makes no representation, express or implied, as to the accuracy, timeliness, or completeness of any such information or with regard to the results to be obtained from its use. Research may contain forward-looking statements, estimates, projections, and opinions with respect to among other things, certain accounting, legal, and regulatory issues the issuer faces and the potential impact of those issues on its future business, financial condition, and results of operations, as well as more generally, the issuer’s anticipated operating performance, access to capital markets, market conditions, assets, and liabilities. Such statements, estimates, projections, and opinions may prove to be substantially inaccurate and are inherently subject to significant risks and uncertainties beyond BSR’s control. All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice, and BSR does not commit to update or supplement any BSR Report or any of the information contained therein.

All Materials Copyrighted; Permitted Sharing

The information on this website, including but not limited to BSR Reports, are copyrighted and the intellectual property of BSR. You agree not to distribute any of the information on this website, whether as a downloaded file, a copy, an image, a reproduction, or a hyperlink to such file, in any manner other than by providing the following hyperlink: bleeckerstreetresearch.com. If you have obtained research published by BSR in any manner other than by downloading a file from the foregoing link, you hereby are on notice of these Terms, agree to these Terms, and agree not to use such research in a manner inconsistent with these Terms.

You further agree that you will not communicate or distribute the contents of BSR Reports and any other information on this site to any other person unless that person has agreed in writing to be bound by these Terms. You understand and agree that if you access this website, download or receive the contents of BSR Reports or other materials on this website as an agent for any other person, you are binding your principal to these Terms.

Limitation of Liability; No Special Damages

Bleecker Street shall not be liable for any claims, losses, costs, or damages of any kind, including direct, indirect, punitive, exemplary, incidental, special or consequential damages, arising out of or in any way connected with this website or the BSR Reports. This limitation of liability applies regardless of any negligence or gross negligence of Bleecker Street. You accept all risks in relying on the information and opinions in any report on this website.

Governing Law; Jurisdiction; Arbitration

You agree that any dispute between you and Bleecker Street arising from or related to these Terms, the information on this website, or any BSR Report shall be governed by the laws of the State of New York, without regard to any conflict of law provisions. You knowingly and independently agree to submit to the personal and exclusive jurisdiction of the state and federal courts located in New York, New York and waive your right to any other jurisdiction or applicable law. You agree that any dispute between you and Bleecker Street arising from or related to these Terms, the information on this website, or any BSR Report shall be brought exclusively in binding arbitration conducted in New York, New York by JAMS, before a single arbitrator, under the applicable JAMS rules. You agree that you waive the right to a trial by jury in any action or proceeding in any jurisdiction between you and Bleecker Street.

No Waiver; Validity

The failure of Bleecker Street Research LLC to exercise or enforce any right or provision of these Terms of Service shall not constitute a waiver of this right or provision. If any provision of these Terms of Service is found by a court of competent jurisdiction to be invalid, the parties nevertheless agree that the court should endeavor to give effect to the parties intentions as reflected in the provision and rule that the other provisions of these Terms of Service remain in full force and effect, in particular as to the foregoing governing law and jurisdiction provision.

One-Year Limitations Period

You agree that regardless of any statute or law to the contrary, any claim or cause of action arising out of or related to the use of this website or the material herein must be filed within one year after such claim or cause of action arose or be forever barred.